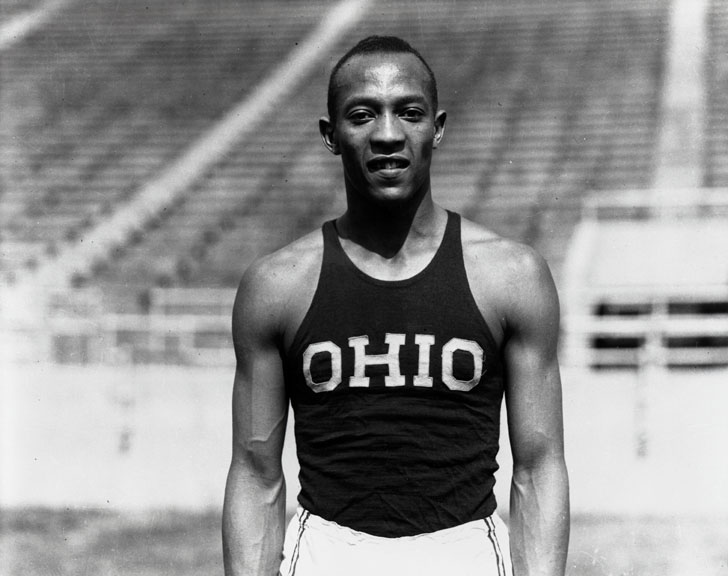

James Cleveland “Jesse” Owens (September 12, 1913 – March 31, 1980) was an American track and field athlete who specialized in the sprints and the long jump. He participated in the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, Germany, where he achieved international fame by winning four gold medals: one each in the 100 meters, the 200 meters, the long jump, and as part of the 4×100 meter relay team. He has the Jesse Owens Award accolade named after him in honor of his significant career.

James Cleveland Owens was born the seventh of eleven children of Henry and Mary Emma Owens in Oakville, Alabama on September 12, 1913. “J.C.”, as he was called, was nine when the family moved to Cleveland, Ohio for better opportunities, as part of the Great Migration, when 1.5 million African Americans left the segregated South. His new teacher nicknamed him Jesse. When she asked his name to enter in her roll book, he said J.C., but because of his strong Southern accent, she thought he said “Jesse”. The name took and he was known as Jesse Owens for the rest of his life

As a boy and youth, Owens took different jobs in his spare time: he delivered groceries, loaded freight cars and worked in a shoe repair shop. During this period, Owens realized that he had a passion for running. Throughout his life, Owens attributed the success of his athletic career to the encouragement of Charles Riley, his junior-high track coach at Fairmount Junior High. Since Owens worked in a shoe repair shop after school, Riley allowed him to practice before school instead.

Owens first came to national attention when he was a student of East Technical High School in Cleveland; he equaled the world record of 9.4 seconds in the 100-yard (91 m) dash and long-jumped 24 feet 9 ½ inches (7.56 m) at the 1933 National High School Championship in Chicago. Owens’s record at East Technical High School directly inspired Harrison Dillard to take up track sports.

Owens attended the Ohio State University after employment was found for his father, ensuring the family could be supported. Affectionately known as the “Buckeye bullet,” Owens won a record eight individual NCAA championships, four each in 1935 and 1936. (The record of four gold medals at the NCAA was equaled only by Xavier Carter in 2006, although his many titles also included relay medals.) Though Owens enjoyed athletic success, he had to live off campus with other African-American athletes. When he traveled with the team, Owens was restricted to ordering carry-out or eating at “black-only” restaurants. Similarly, he had to stay at “blacks-only” hotels. Owens did not receive a scholarship for his efforts, so he continued to work part-time jobs to pay for school.

Owens’s greatest achievement came in a span of 45 minutes on May 25, 1935 at the Big Ten meet in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where he set three world records and tied a fourth. He equaled the world record for the 100-yard (91 m) sprint (9.4 seconds); and set world records in the long jump (26 feet 8¼ inches (8.13 m), a world record that would last 25 years); 220-yard (201.2 m) sprint (20.3 seconds); and 220-yard (201.2m) low hurdles (22.6 seconds, becoming the first to break 23 seconds). In 2005, NBC sports announcer Bob Costas and University of Central Florida professor of sports history Richard C. Crepeau both chose these wins on one day as the most impressive athletic achievement since 1850.

Owens was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha, the first intercollegiate Greek-letter organization established by and for African Americans.

In 1936, Owens arrived in Berlin to compete for the United States in the Summer Olympics. Adolf Hitler was using the games to show the world a resurgent Nazi Germany. He and other government officials had high hopes that German athletes would dominate the games with victories (the German athletes achieved a “top of the table” medal haul). Meanwhile, Nazi propaganda promoted concepts of “Aryan racial superiority” and depicted ethnic Africans as inferior.

Owens surprised many by winning four gold medals: On August 3, 1936 he won the 100m sprint, defeating Ralph Metcalfe; on August 4, the long jump (later crediting friendly and helpful advice from Luz Long, the German competitor he ultimately defeated); on August 5, the 200m sprint; and, after he was added to the 4 x 100 m relay team, he won his fourth on August 9 (a performance not equaled until Carl Lewis won gold medals in the same events at the 1984 Summer Olympics).

Just before the competitions, Owens was visited in the Olympic village by Adi Dassler, the founder of the Adidas athletic shoe company. He persuaded Owens to use Adidas shoes, the first sponsorship for a male African-American athlete.

The long-jump victory is documented, along with many other 1936 events, in the 1938 film Olympia by Leni Riefenstahl.

On the first day, Hitler shook hands only with the German victors and then left the stadium. Olympic committee officials insisted Hitler greet every medalist or none at all. Hitler opted for the latter and skipped all further medal presentations. On reports that Hitler had deliberately avoided acknowledging his victories, and had refused to shake his hand, Owens recounted:

Owens was cheered enthusiastically by 110,000 people in Berlin’s Olympic Stadium; on the street, Germans sought his autograph. Owens was allowed to travel with and stay in the same hotels as whites, while at the time blacks in many parts of the United States were denied equal rights. After a New York City ticker-tape parade of Fifth Avenue in his honor, Owens had to ride the freight elevator at the Waldorf-Astoria to reach the reception honoring him.

Owens said, “Hitler didn’t snub me—it was FDR who snubbed me. The president didn’t even send me a telegram.” Jesse Owens was never invited to the White House nor bestowed honors by presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) or his successor Harry S. Truman during their terms. In 1955, President Dwight D. Eisenhower honored Owens by naming him an “Ambassador of Sports.”