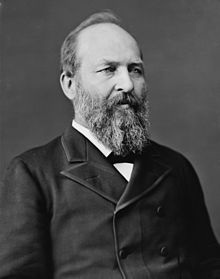

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) served as the 20th President of the United States, after completing nine consecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. Garfield’s accomplishments as President included a controversial resurgence of Presidential authority above Senatorial courtesy in executive appointments; energizing U.S. naval power; and purging corruption in the Post Office Department. Garfield made notable diplomatic and judiciary appointments, including a U.S. Supreme Court justice. Garfield appointed several African-Americans to prominent federal positions.

Garfield was raised in humble circumstances on an Ohio farm by his widowed mother and elder brother, next door to their cousins, the Boyntons, with whom he remained very close. He worked at many jobs to finance his higher education at Williams College, Massachusetts, from where he graduated in 1856.

A year later, Garfield entered politics as a Republican, after campaigning for the party’s antislavery platform in Ohio. He married Lucretia Rudolph in 1858, and in 1860 was admitted to practice law while serving as an Ohio State Senator (1859–1861). Garfield opposed Confederate secession, served as a Major General in the Union Army during the American Civil War, and fought in the battles of Middle Creek, Shiloh and Chickamauga. He was first elected to Congress in 1862 as Representative of the 19th District of Ohio.

Throughout Garfield’s extended Congressional service after the Civil War, he fervently opposed the Greenback, and gained a reputation as a skilled orator. He was Chairman of the Military Affairs Committee and the Appropriations Committee and a member of the Ways and Means Committee. Garfield initially agreed with Radical Republican views regarding Reconstruction, then favored a moderate approach for civil rights enforcement for Freedmen. In 1880, the Ohio legislature elected him to the U.S. Senate; in that same year, the leading Republican presidential contenders – Ulysses S. Grant, James G. Blaine and John Sherman – failed to garner the requisite support at their convention. Garfield became the party’s compromise nominee for the 1880 Presidential Election and successfully campaigned to defeat Democrat Winfield Hancock in the election. He is thus far the only sitting Representative to have been elected to the presidency.

Garfield’s presidency lasted just 200 days—from March 4, 1881, until his death on September 19, 1881, as a result of being shot by assassin Charles J. Guiteau on July 2, 1881. Only William Henry Harrison’s presidency, of 32 days, was shorter. Garfield was the second of four United States Presidents who were assassinated. President Garfield advocated a bi-metal monetary system, agricultural technology, an educated electorate, and civil rights for African-Americans. He proposed substantial civil service reform, eventually passed by Congress in 1883 and signed into law by his successor, Chester A. Arthur, as the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act.

Childhood

James Garfield was born the youngest of five children on November 19, 1831, in a log cabin in Orange Township, now Moreland Hills, Ohio. Next door lived his uncle Amos and aunt Alpha Boynton. The families were very close as Amos was James’ father’s half brother, and Alpha was his mother’s sister. James and his Boynton cousins cherished their memories of childhood together.

His father, Abram Garfield, known locally as a wrestler, died when Garfield was 17 months old. Of part Welsh ancestry, he was reared and cared for by his mother, Eliza (née Ballou), who said, “He was the largest babe I had and looked like a red Irishman.” Garfield’s parents joined Disciples of Christ Church, which profoundly influenced their son. Garfield was able to receive rudimentary education at a village school in Orange, listening and discussing books read. Garfield knew he needed money to advance his learning.

At age 16, he struck out on his own, drawn seaward by dreams of being a seaman, and got a job for six weeks as a canal driver near Cleveland. Illness forced him to return home and, once recuperated, he began school at Geauga Seminary, where he became keenly interested in academics, both learning and teaching. Garfield worked as a janitor, bell ringer, and carpenter to support himself financially at the Geauga Seminary, at Chester, Ohio., Garfield later said of this early time, “I lament that I was born to poverty, and in this chaos of childhood, seventeen years passed before I caught any inspiration…a precious 17 years when a boy with a father and some wealth might have become fixed in manly ways.” In 1849, he accepted an unsought position as a teacher, and thereafter developed an aversion to what he called “place seeking,” which became, he said, “the law of my life.” In 1850 Garfield resumed his church attendance and was baptized.

Education, marriage and early career

From 1851 to 1854, he attended the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (later named Hiram College) in Hiram, Ohio. While at Eclectic, he was most interested in the study of Greek and Latin, and he was also engaged to teach. He developed a regular preaching circuit at neighboring churches, in some cases earning a gold dollar per service. Garfield then enrolled at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, where he joined the Delta Upsilon fraternity and graduated in 1856 as an outstanding student. Garfield was quite impressed with the college President, Mark Hopkins, about whom he said, “The ideal college is Mark Hopkins on one end of a log with a student on the other.” Garfield earned a reputation as a skilled debater and was made President of the Philogian Society and Editor of the Williams Quarterly.

After preaching briefly at Franklin Circle Christian Church (1857–58), Garfield gave up on that vocation and applied for a job as principal of a high school in Poestenkill, New York. After another applicant had been chosen, he returned to teach at the Eclectic Institute. Garfield was an instructor in classical languages for the 1856–1857 academic year and was made Principal of the Institute from 1857 to 1860, successfully restoring it to viability after it had fallen on hard times. During this time, Garfield revealed himself to be sympathetic with the views of moderate Republicans, though he was not yet a party man. While he did not consider himself an abolitionist, he was opposed to slavery. After Garfield finished his education, between the 1857 and 1858 elections, he began his career in politics as a “vigorous” stump speaker in support of the Republican Party and their anti-slavery cause. In 1858, a migrant freethinker and evolutionary named Denton challenged him to a debate (Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species was published the next year). The debate, which lasted over a week, was considered as won convincingly by Garfield.

Garfield’s first romantic interest was Mary Hubbell in 1851, but it lasted only a year, with no formal engagement. On November 11, 1858, he married Lucretia Rudolph, known as “Crete” to friends, and a former star Greek pupil of Garfield’s. They had seven children (five sons and two daughters): Eliza Arabella Garfield (1860–63); Harry Augustus Garfield (1863–1942); James Rudolph Garfield (1865–1950); Mary Garfield (1867–1947); Irvin M. Garfield (1870–1951); Abram Garfield (1872–1958); and Edward Garfield (1874–76). One son, James R. Garfield, followed him into politics and became Secretary of the Interior under President Theodore Roosevelt.

Garfield gradually became discontented with teaching and began to study law in 1859. He was admitted to the Ohio bar in 1861. Before admission to the bar, he was invited to enter politics by local Republican Party leaders upon the death of Cyrus Prentiss, the presumed nominee for the state senate seat for the 26th District in Ohio. He was nominated by the party convention and then elected an Ohio state senator in 1859, serving until 1861. Garfield’s signature effort in the state legislature was a bill providing for the state’s first geological survey to measure its mineral resources. His initial observations about the nation leading up to the Civil War were that secession was quite inconceivable. His response was in part a renewed zeal for the July 4 celebrations in 1860.

After Abraham Lincoln’s election, Garfield was more inclined to arms than negotiations, saying, “Other states may arm to the teeth, but if Ohio so much as cleans her rusty muskets, it is said to have offended our brethren in the South. I am weary of this weakness.” On February 13, 1861, the newly elected President Lincoln arrived in Cincinnati by train to make a speech. Garfield observed that Lincoln was “distressingly homely”, yet had “the tone and bearing of a fearless, firm man.”

Military career

At the start of the American Civil War, Garfield quickly grew frustrated with his vain efforts to obtain an officer’s commission in the Union Army. Ohio Governor William Dennison, Jr. charged him with a mission to travel to Illinois to acquire musketry and to negotiate with the Governors of Illinois and Indiana for the consolidation of troops. In the summer of 1861 he was finally commissioned a Lt. Colonel in the Union Army and given command of the 42nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry.

General Don Carlos Buell assigned Colonel Garfield the task of driving Confederate forces out of eastern Kentucky in November 1861, giving him the 18th Brigade for the campaign. In December, he departed Catlettsburg, Kentucky, with the 40th Ohio Infantry, the 42nd Ohio Infantry, the 14th Kentucky Infantry, and the 22nd Kentucky Infantry, as well as the 2nd (West) Virginia Cavalry and McLoughlin’s Squadron of Cavalry. The march was uneventful until Union forces reached Paintsville, Kentucky, on January 6, 1862, where Garfield’s cavalry engaged the Confederates at Jenny’s Creek. Garfield artfully positioned his troops so as to deceive Marshall into thinking that he was outnumbered, when in fact he was not. The Confederates, under Brig. Gen. Humphrey Marshall, withdrew to the forks of Middle Creek, two miles (3 km) from Prestonsburg, Kentucky, on the road to Virginia. Garfield attacked on January 9, 1862. At the end of the day’s fighting the Confederates withdrew from the field, but Garfield did not pursue them, opting instead to withdraw to Prestonsburg so he could resupply his men. His victory brought him early recognition and he was promoted to the rank of brigadier general on January 11.

Garfield later commanded the 20th Brigade of Ohio under Buell at the Battle of Shiloh, where he led troops in an attempt, delayed by weather, to reinforce Maj Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, after a surprise attack by Confederate General Albert S. Johnston. He then served under Thomas J. Wood in the Siege of Corinth, where he assisted in the pursuit of Confederates in retreat by the overly cautious Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, which resulted in the escape of Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard and his troops. This engendered in the furious Garfield a lasting distrust of the training at West Point. Garfield’s philosophy of war in 1862—to aggressively carry the war to Southern civilians—was not then shared by the Union leadership. The tactic was later adopted and demonstrated in the campaigns of Generals Sherman and Sheridan.

Garfield made the following comment in 1862 concerning slavery: “…if a man is black, be he friend or foe, he is thought best kept at a distance. It is hardly possible God will let us succeed while such enormities are practiced.” That summer his health suddenly deteriorated, including jaundice and significant weight loss. (Biographer Peskin speculated this may have been infectious hepatitis.) Garfield was forced to return home, where his wife nursed him back to health and their marriage was reinvigorated. He returned to duty that autumn and served on the Court-martial of Fitz John Porter. Garfield was then sent to Washington to receive further orders. With great frustration, he repeatedly received tentative assignments, extended and later reversed, to stations in Florida, Virginia and South Carolina. During this period of idleness in Washington waiting for an assignment, Garfield spent much of his time corresponding with old friends and family. An unsubstantiated rumor of an affair caused a brief friction in the Garfield marriage of which Lucretia graciously overlooked.

In the spring of 1863 Garfield returned to the field as Chief of Staff for William S. Rosecrans, commander of the Army of the Cumberland; his influence in this position was greater than usual – with duties extending beyond mere communication to actual management of Rosecrans’s army. Rosecrans, a highly energetic man, had a voracious appetite for conversation, which he deployed when he was unable to sleep; in Garfield he had found “the first well read person in the Army” and thus the ideal candidate for endless discussions through the night. The two became close, and covered all topics, especially religion; Rosecrans, who with his brother had converted from Methodism to Catholicism, succeeded in softening Garfield’s view of Catholicism. Garfield, with his enhanced influence, created an intelligence corps unsurpassed in the Union Army. He also recommended that Rosecrans should replace wing commanders Alexander McCook and Thomas Crittenden due to their prior ineffectiveness. Rosecrans ignored these recommendations, with drastic consequences later, in the Battle of Chickamauga. Garfield crafted a campaign designed to pursue and then trap Confederate General Braxton Bragg in Tullahoma. The army advanced to that point with success, but Bragg retreated toward Chattanooga. Rosecrans then stalled his army’s move against Bragg and made repeated requests for additional troops and supplies. Garfield argued with his superior for an immediate advance, also insisted upon by Lincoln and Rosecrans’s commander, Gen. Halleck. Garfield conceived a plan to conduct a cavalry raid behind Bragg’s line (similar to that Bragg was employing against Rosecrans) which Rosecrans approved; the raid, led by Abel Streight, failed, due in part to poor execution and weather. Garfield’s detractors later claimed his concept was flawed. To address the continued dispute over whether to advance, Rosecrans called a war council of his generals; 10 of the 15 were opposed to the move, with Garfield voting in favor. Nevertheless Garfield, in an unusual move, drew up a report of the council’s deliberations, and thus convinced Rosecrans to proceed with an advance against Bragg.

At the Battle of Chickamauga, Rosecrans issued an order which sought to fill a gap in his line, but which actually created one. As a result, his right flank was routed. Rosecrans concluded that the battle was lost and headed for Chattanooga to establish a defensive line. Garfield, however, thought that part of the army had held and, with Rosecrans’s approval, headed across Missionary Ridge to survey the Union status. Garfield’s hunch was correct; his ride became legendary, while Rosecrans’ error reinforced critical opinions about his leadership. While Rosecrans’s army had avoided complete loss, they were left in Chattanooga surrounded by Bragg’s army. Garfield sent a telegram to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton alerting Washington to the need for reinforcements to avoid annihilation. As a result, Lincoln and Halleck succeeded in delivering 20,000 troops to Chattanooga by rail within nine days. One of Grant’s early decisions upon assuming command of the Union Army was to replace Rosecrans with George H. Thomas. Garfield was issued orders to report to Washington, where he was promoted to Major General; shortly thereafter he gave an unambiguously abolitionist speech in Maryland. He was unsure of whether he should return to the field or assume the Ohio congressional seat he had won in October 1862. After a discussion with Lincoln, he decided in favor of the latter and resigned his commission. According to historian Jean Edward Smith, Grant and Garfield had a “guarded relationship”, since Grant put Thomas in charge of the Army of the Cumberland, rather than Garfield, after Rosecrans was dismissed.

Garfield communicated his frustration with Rosecrans in a confidential letter to his friend Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase. Garfield’s detractors later used this letter, which Chase never personally disclosed, to foster widespread criticism of Garfield as a betrayer, despite the fact that Halleck and Lincoln shared the same concerns over Rosecrans’s reluctance to attack, and that Garfield had openly conveyed his concerns to Rosecrans. In later years, Charles Dana of the New York Sun allegedly had sources indicating that Garfield had publicly stated that Rosecrans had fled the battlefield during the Battle of Chickamauga. According to biographer Peskin, the credibility of the information and the sources used are questionable. According to historian Bruce Catton, Garfield’s statements influenced the Lincoln administration to find a replacement for Rosecrans.

Presidential election of 1880

The Ohio legislature had just chosen Garfield in 1879 for the U.S. Senate seat when a faint movement began for Garfield as the next Republican nominee for President to succeed Hayes – he had chosen not to stand for re-election. In early 1880 Garfield endorsed John Sherman for the party’s Presidential nomination in exchange for Sherman’s earlier support of Garfield for the Senate. However, at the outset of the Republican convention, a deadlock ensued between supporters of former President Grant, James G. Blaine, and Sherman; the delegates began to look to Garfield as an optimal compromise choice. Garfield eloquently defended dissenting West Virginia delegates in his speech against Sen. Conkling’s convention rule that stated all state delegates must vote unanimously for only one candidate. After over thirty ballots, the vote totals for the leading contenders were within five votes of where they had been on the first ballot. With the 34th ballot, Wisconsin began the break to Garfield that would end with his nomination as the party’s Presidential candidate. Garfield’s capture of the 1880 nomination for the Presidency over the prominent contenders was considered historic. Garfield defeated the front runner Ulysses S. Grant’s controversial third term bid for the nomination.

Thomas Nichol, Wharton Barker, and Benjamin Harrison were widely considered to be the primary architects of Garfield’s ascendancy during the convention, but no one could have controlled this unpredictable outcome for such a dark horse—one who had personally objected at every step. To obtain Republican Stalwart support for the ticket, former New York customs collector Chester A. Arthur was chosen as the vice-presidential nominee and Garfield’s running mate.

In the wake of such a fractured convention, the outlook for Garfield’s campaign was less than optimal. In an effort to heal residual wounds from the convention, Garfield traveled to New York to bring the party’s warring factions together in what was called the “New York Conference”, and what was considered a personal triumph. This was the only trip of consequence which Garfield made away from home during the campaign. Powerful railroad interests were courted by the party in the wake of Supreme Court decisions that had been adverse to their interests. After assuring them that they would have the President’s ear in such matters, Garfield gained their support.

Another issue in the Election of 1880 was Chinese immigration; those in the West, particularly California, were opposed to Chinese immigration, considered antithetical to normal economic growth in that region. Easterners, such as Senator George F. Hoar, took a more philosophical and religious stand in favor of Chinese immigration. On the eve of the election the Democrats widely published a letter—allegedly over Garfield’s signature—which favored Chinese immigration, in an attempt to affect the outcome of the election. The timing of the letter’s publication, some obvious inconsistencies in the letter’s wording, and even the handwriting itself, led many to believe it to be a forgery.

In the general election, Garfield defeated the Democratic candidate Winfield Scott Hancock, another distinguished former Union Army general, by 214 electoral votes to 155. The popular vote had a plurality of just over 7,000 votes out of more than 8.89 million cast. He became the only man ever to be elected to the Presidency directly from the House of Representatives and was for a short period a sitting Representative, Senator-elect, and President-elect.

Presidency 1881

As usual, the votes had barely been counted when office-seekers besieged Garfield. There were at this point over 100,000 federal government employees, most of whom expected to be replaced when a new administration took over; the President-elect described the situation as “a barrage of fear and greed.” Garfield was convinced the only answer was some type of civil service reform. President Garfield had a mere four months to establish his presidency before he was shot by Charles J. Guiteau, a deranged political office seeker, on July 2, 1881. Garfield lived for 80 days after he was shot, but was unable to govern. During his limited time in office, Garfield managed to initiate reform of the Post Office Department’s notorious “star route” rings and reassert the superiority of the office of the President over the U.S. Senate on the issue of executive appointments. Garfield made four federal court appointments and filled one vacancy on the U.S. Supreme Court. His inaugural address set the agenda for his Presidency, but he did not live long enough to implement most of these policies. Garfield’s persistent call for civil service reform, however, was fulfilled with the passage of the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act, enacted by Congress and signed by President Chester A. Arthur in 1883. Indeed, Garfield’s assassination was the primary motivation for the reform bill’s passage. Garfield’s single executive order was to provide government workers the day off on May 30, 1881, in order to decorate the graves of those who died in the Civil War. At the time of Garfield’s residence in the office, the President’s annual salary was $50,000, which would be largely consumed for the operation of the White House. And, despite rumors of ill-gotten wealth, Garfield could afford no horse and buggy to park in the White House stable, but accepted Hayes’ offer of his own quite used-up rig.

Assassination

On the morning of July 2, 1881, President Garfield was on his way to his alma mater, Williams College, where he was scheduled to deliver a speech. Garfield was accompanied by James G. Blaine, Robert Todd Lincoln, and his two sons, James and Harry. As the President was walking through the Sixth Street Station of the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad in Washington at 9:30 am, he was shot twice from behind, once across the arm and once in the back, by an assassin, Charles J. Guiteau, a rejected and disillusioned Federal office seeker. Secretary Blaine had denied Guiteau, having no qualifications, a Federal appointment as the United States consul in Paris and had banned him from the White House for his aggressive behavior in seeking an appointment. Guiteau believed as well that a short speech he had partially presented before a small group of people during the presidential election campaign was in fact the cause of Garfield’s election to the presidency and which, therefore, justified his appointment. When the appointment did not materialize, Guiteau believed he, the Republican Party, and the country had been betrayed and that God repeatedly told him (Guiteau) that he could save the party and the nation if President Garfield was “removed.” Guiteau stalked Garfield for weeks, armed with a .44 caliber Webley Bulldog revolver. As Guiteau was being arrested after the shooting, he repeatedly said, “I am a Stalwart of the Stalwarts! I did it and I want to be arrested! Arthur is President now!” This very briefly led to unfounded suspicions that Arthur or his supporters had put Guiteau up to the crime. Guiteau also believed he would be acquitted of any crime and be elected President after the trial.

Garfield exclaimed immediately after he was shot, “My God, what is this?” One bullet grazed Garfield’s arm; the second bullet was thought later to have possibly lodged near his liver but could not be found; and upon autopsy was located behind the pancreas. Though Alexander Graham Bell specifically devised a metal detector to find the bullet, the device’s signal was thought to be distorted by the metal bed springs. Later the detector was proved to work perfectly and would have found the bullet had Dr. Doctor Willard Bliss (who was a Doctor of Medicine but whose given name was also “Doctor”) allowed Bell to use the device on Garfield’s left side as well. Garfield became increasingly ill over a period of several weeks due to infection, which caused his heart to weaken. He remained bedridden in the White House with fever and extreme pain. As the heat of summer became more oppressive for the stricken President, a Navy engineer, with the help of Simon Newcomb, installed in Garfield’s room what may have been the world’s first air conditioner. An air blower was installed over a chest containing 6 tons of ice, with the air then dried by conduction through a long iron box filled with cotton screens, and connected to the room’s heat vent. This device was at times capable of reducing the air temperature to 20°F (11°C) below the outside temperature.

Sympathies for President Garfield poured out across the nation and the world. Condolences came from the King of Italy and the Rothschilds. Democratic Kentucky governor Luke P. Blackburn ordered a day of “public fasting and prayer”.

On September 6 the ailing President was moved to the Jersey Shore in the vain hope that the fresh air and quiet there might aid his recovery. In a matter of hours, local residents put down a special rail spur for Garfield’s train; some of the ties are now part of the Garfield Tea House. The beach cottage Garfield was taken to has been demolished.

On Monday, September 19, 1881, at 10:20 p.m. President Garfield suffered a massive heart attack and a ruptured splenic artery aneurysm, following blood poisoning and bronchial pneumonia. Garfield’s chief doctor, Dr. Doctor Willard Bliss, had unsuccessfully attempted to revive the fading President with restorative medication. Mrs. Garfield, having leaned over Garfield, kissed his brow and exclaimed, “Oh! Why am I made to suffer this cruel wrong?” Garfield was pronounced dead at 10:35 p.m. by Dr. Bliss in the Elberon section of Long Branch, New Jersey. Mrs. Garfield remained with her dead husband for over an hour until prompted to leave the room. The wounded President died exactly two months before his 50th birthday, the second youngest age of death for a U.S. president after John F. Kennedy, who was also assassinated. During the 80 days between his shooting and death, his only official act was to sign an extradition paper. His final words: “My work is done.” He was survived by his mother Eliza Ballou Garfield, who died on January 21, 1888.

According to some historians and medical experts Garfield might have survived his wounds had the doctors attending him had at their disposal today’s medical research, techniques, and equipment. Standard medical practice at the time dictated that priority be given to locating the path of the bullet. Several of his doctors inserted their unsterilized fingers into the wound to probe for the bullet, a common practice in the 1880s. American doctors had not fully accepted the sterilization technique implemented by Joseph Lister during the 1860s. Historians agree that massive infection was a significant factor in President Garfield’s demise. Biographer Peskin stated that medical malpractice did not contribute to Garfield’s death; the inevitable infection and blood poisoning that would ensue from a deep bullet wound resulted in multiple organ damage and spinal bone fragmentation.

Guiteau was formally indicted on October 14, 1881, for the murder of the President. Although Guiteau’s counsel argued the insanity defense, due to his odd character, the jury found him guilty on January 5, 1882, and he was sentenced to death. Guiteau may have had syphilis, a disease that causes physiological mental impairment. Guiteau was executed on June 30, 1882. He was also heard to claim that important men in Europe put him up to the task, and had promised to protect him if he were caught.

President Garfield’s murder by a deranged federal office seeker awakened public awareness and prompted Congress to pass civil service reform legislation. Senator George H. Pendleton, a Democrat from Ohio, launched a reform effort that resulted in President Chester A. Arthur signing into law the Pendleton Act in January 1883. This act reversed the “spoils system” where office seekers paid or gave political service in order to obtain or keep federally appointed positions. Under the Pendleton Act, office appointments were awarded on merit and competitive examination. The law made illegal the long-time practice of giving money or service to obtain a federal appointment. To ensure the reform was implemented, Congress and President Arthur established and funded the Civil Service Commission. The Pendleton Act, however, only covered 10% of federal government workers. President Arthur, who was previously known for having been a “veteran spoilsman”, became an avid civil service reformer after President Garfield’s assassination.

Garfield’s stress on the importance of education for African Americans served as a catalyst for their advancement. As a scholar president, pre-dating Woodrow Wilson, Garfield was an avid reader, having a 3,000-book library that included Horace, Shakespeare, Goethe, Tennyson, and Froude’s history of England.