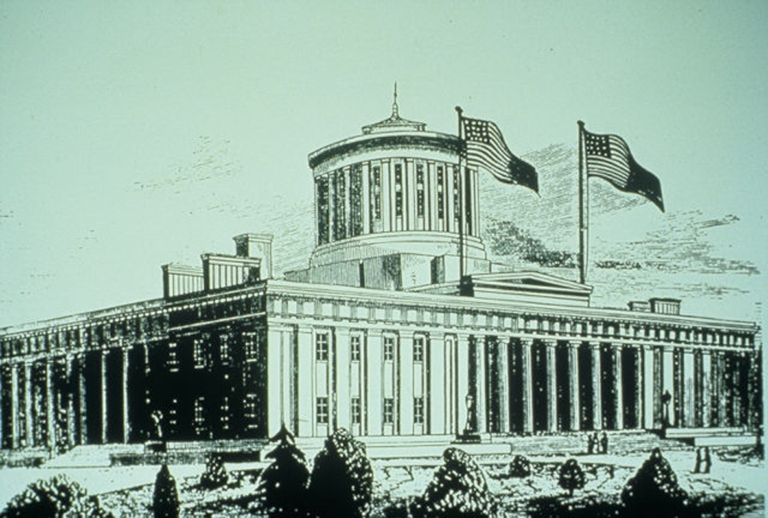

The Statehouse is considered to be one of the most significant architectural accomplishments of the early republic. Its Greek Revival Doric architectural details and proportions give the impression of permanence, elegance and grandeur deserved by the original State Legislature who passed a law on January 26, 1838 to build the new Statehouse. Restored to its 1861 appearance, the Ohio Statehouse maintains its historic character as it continues to function as the center of state government in Ohio.

The Ohio Statehouse is more than a monument to our past; it’s where history happens. Visit our historical destinations, draw inspiration from the artwork and monuments, and witness the making of history through the modern lawmaking process during your trip. We hope to see you at the People’s House very soon!

Overview

A brief history of the Statehouse and its renovation

Areas To Explore

An interactive map of the Statehouse grounds and building

Planning a Visit

School groups and the general public can see the Statehouse in person

Fun Facts

Statehouse tidbits that you may not know

A brief History of the Statehouse

The Ohio Statehouse is situated on a 10-acre parcel of land that was donated by John Kerr, Lyne Starling, John Johnston and Alexander McLaughlin, four prominent landholders in the Franklinton area on the west side of the Scioto River.

The initial design was arrived at through a design competition. Construction actively began on July 4, 1839 with the ceremonial laying of the cornerstone. The structure would be completed much later, in 1861. Prison labor from the Ohio Penitentiary was used to construct the foundation and ground floors of the building. Objections from skilled tradesman, who felt they were losing out on good-paying jobs, brought about changes in hiring practices for the remainder of the construction.

The Statehouse is built in the Greek Revival style, a type of design based on the buildings of Ancient Greece and very popular in the U.S. during the early and mid-1800s. Because the city-states of Ancient Greece were the birthplace of democracy, the style had great meaning in the young American nation. Greek Revival was simple and straightforward and looked nothing like the Gothic Revival buildings popular in Europe during the same period. The broad horizontal mass of the Statehouse and the even and regular rows of columns resemble such buildings as the Parthenon in Athens. It is a masonry building, consisting largely of Columbus limestone. The limestone was taken from a quarry on the west banks of the Scioto River. The stone of the Statehouse foundation is more than 18 feet deep.

During the course of the Statehouse’s construction, 22 years would pass, but it would not be a period of non-stop work. Construction would cease during the harsh winter months, and as the project would exceed its budget, there would often be halts in construction as new funding was arranged. The longest gap in construction came about when the legislation making Columbus the state capital was due to expire. There was a eight-year lapse (1840-1848) when no work was done on the Statehouse. The completed basement and foundations were actually filled in with soil and Capitol Square was used as a pasture.

There would be seven architects of the building. One of the most notable Statehouse architects was Ohio-born Nathan B. Kelley who lived and worked most of his life in Columbus. In contrast to the simple and straightforward exteriors of the building, Kelley used a great deal of ornament and detail on the building’s interiors. Kelley took these steps because he felt an important building such as the Statehouse should look and feel imposing and impressive. He was fired because the commissioners overseeing the project felt these extra flourishes were both too expensive and too lavish for the original design of the building.

Nathan B. Kelley was responsible for many of the architectural improvements of the Statehouse as well. It was Kelley who discovered that the Statehouse had been planned without any heating or ventilation system. He corrected this problem by building brick walls inside the building that he referred to as “air sewers” that would function like ductwork in a modern heating system, moving air throughout the building. The system is based on forced ventilation, which pushes air through the building, a common modern concept but ahead of its time in Kelley’s day. The system was so efficient that attempts of “renovators” to seal off these ventilation ducts would be largely unsuccessful because the covers eventually blew off.

The Statehouse was opened to legislators and the public in 1857 when legislators began meeting in their respective chambers and most of the executive offices were occupied. The Statehouse was finally completed in 1861.

The Statehouse has been designated a National Historic Landmark by the Secretary of the U.S. Department of the Interior (1978). This honor recognizes the long history of the building and the continued role it will have in the life and lawmaking of the state of Ohio. During the restoration project in the early 1990s, original graffiti sketched by some of the Ohio Penitentiary prisoners was uncovered. One sketch is a profile of a man’s face with the word “Badger” scrawled above it. By searching records at the Ohio Historical Society, the restoration team was able to locate information about Ephraim Badger, who was imprisoned from 1846-1849 for burglary. His record states that he was pardoned in 1849 “for service to the state.”

Historical Photos

Restoration Begins

As all seven of the architects originally intended, the Ohio Statehouse should not only serve as an edifice of government, but it should also be a showcase of our culture and heritage as Ohioans and Americans.

The Capitol Square restoration master plan was released in October 1989. A very important reason to renovate was the mere fact that the buildings on Capitol Square had fallen into a terrible state of disrepair and, in many cases, were unsafe.

Not to Code

Neither the Statehouse nor the Senate Building conformed to 20th-century building codes. In fact, neither building had a fire sprinkler system. Wiring and other mechanical delivery systems were left exposed. The electrical system was inadequate for the demands of modern office equipment and computers. Asbestos was present in the buildings. The roofs leaked. Many rooms lacked safe exit routes, and there were numerous dead-end corridors, in which people could become trapped in the event of an emergency.

Small Office Space

In addition, most of the changes that had been made over the years destroyed the historic and aesthetic qualities of the structures. Several two-story spaces were subdivided with intermediate floors. There were as many as seven floors in the Statehouse where there used to be three. Most rooms were “renovated” with drop ceilings, which often times hid skylights and other original decorative work. In some rooms, the ceiling had been dropped as many as three times.

The Statehouse’s steam heating system was inefficient because it was designed for large rooms which had been partitioned into numerous smaller ones. To cool the building in the summer months, there were 96 separate air-conditioning systems in the Statehouse and Senate Building. Occasionally, these units exhausted into other rooms, which in turn needed two or more air-conditioning units to keep cool. In the Statehouse, every time additional office space was needed, rooms were subdivided until a building originally designed to hold 53 rooms contained 317.

The Grounds

The Capitol Square grounds, a 10-acre public park that surrounded the Statehouse, displayed cracked pavement, dying trees, no access for the disabled and inadequate facilities for special events.