A mile north of Van Meter and a couple of miles east, down a gravel road, sits the old family farm. The red barn built in 1886 still stands, now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It was here on a stretch of land between the barn and the farm house that Bill Feller set up a makeshift backstop. It was here that he and his son Bob played catch in the 1920s and ’30s: where young Bob learned his windmill windup, where he developed both his blazing fast ball and his bending curve ball. It was here that Bob Feller awakened in his son a passion for the playing field and a gift for baseball.

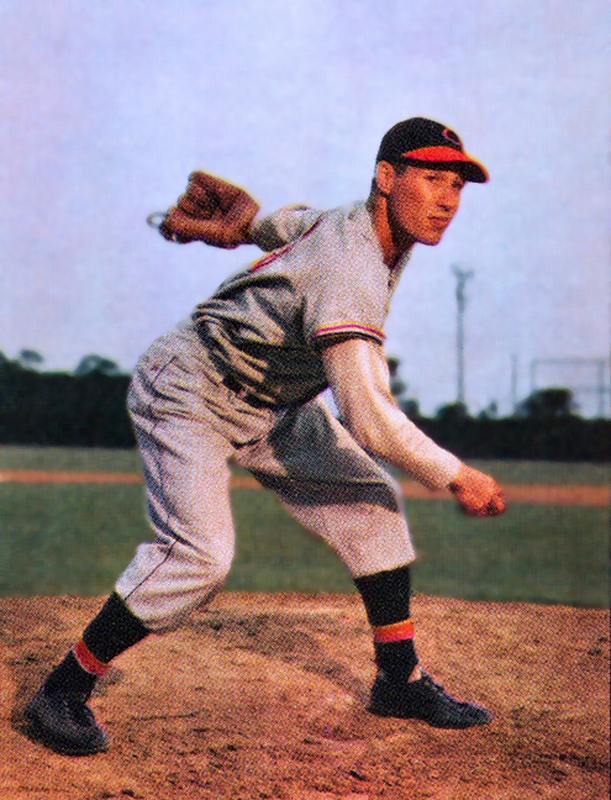

Like Roy Hobbs, Robert Redford’s fictional character in The Natural, young Bob Feller had more god given talent than most baseball players could ever dream of. And, like Hobbs, Feller learned to pitch by throwing to his dad on their farm near Van Meter. While other rural boys were working in the fields, Feller spent the summer vacation before his senior year of high school pitching for the Cleveland Indians.

No teen has ever matched Feller’s explosive debut on the major league scene. The seventeen – year – old rookie vaulted into the headlines when he struck out eight St. Louis Cardinals in three innings during a July 1936 exhibition. For an encore, the kid struck out fifteen batters in pitching the Indians to a victory over the St. Louis Browns that August. In September, the rookie blazed his 100-mile-per-hour fast ball past the Philadelphia Athletics to strike out seventeen batters. This performance put “Rapid Robert” Feller beside Dizzy Dean as co-holder of the major league strike out record. Before the 1936 season was over, the New York Times reported that Feller’s name was “on the tongues of a million fans.”

The fanfare for Feller grew. Time put Feller on it’s April 19, 1937, cover. NBC radio jumped on the Feller bandwagon, covering the young player’s graduation from Van Meter High School “live” on its national radio network. His fastball starred in newsreels, racing against a speeding motorcycle. Feller’s glory was magnified by his World War II service. After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. Feller was the first major leaguer to enlist in the military.

Before Feller was out of his teens_ he had struck out 18 Detroit Tigers in 1938 to set the strikeout record for both leagues. By the time he retired in 1956, Feller had won 266 games. hurled 3 no-hitters, and earned a place in baseball’s Hall of Fame. Bob Feller, it seemed, would be remembered forever. But as the great sports reporter Grantland Rice waxed poetically in “Casey’s revenge, ” “Fame is fleeting as the wind, and glory fades away.” As proof of this maxim, the current generation shows little recognition of Feller. A recent online search revealed that both Wikipedia and DesMoinesRegister.com omitted Feller from their list of “Famous Iowans.”

Today, the 88-year-old Feller has outlived most of his former Cleveland Indians teammates and most of his schoolmates from Van Meter’s class of 1937. He spends much of his time these days with his wife, Anne, on their acreage in Gates Mills, Ohio, But occasionally Feller returns to where his legend endures.

When I entered the basement of the Bob Feller Museum in Van Meter last summer, my eyes zoomed in on the barrel-chested man autographing baseballs. He sat at a table with a box of baseballs on his left and a stack of Bob Feller’s Little Black Book of Baseball Wisdom on his right. He gripped each baseball tightly so it didn’t move while he scribbled his name on it. The man bore a resemblance to a ball player whose Topps baseball card I had acquired in 1956 Same dimpled chin. Same toothy smile.

“Hello, Bob,” I said.

Feller looked up from his work and shook my hand. “Pull up a chair,” he said.

Feller seems in fine shape. The former farm boy from Van Meter is aging as gracefully as he used to pitch. His six-foot frame and a husky upper body make him seem powerful enough to rear back and fire his fastball. White hair has replaced the jet-black hair of his youth. Wire-rimmed glasses now cover the eyes that used to glare fearlessly at major league hitters. A paunch protrudes over his belt. A couple of benign melanoma spots mark his face–possibly caused by 28 crossings of the equator aboard the USS Alabama, chasing the Japanese off the South Pacific islands during World War ll, surmised Feller.

Retired sports stars often end up coaching, or sometimes selling real estate or running a restaurant. Feller developed a successful insurance business, promoted various products. and contributed something to the community by serving as the chairman of the Ohio March of Dimes. But baseball never left Feller’s life.

“I spend each Spring in fantasy camp,” Feller said “I still throw from the rubber, and I throw the ball as hard as I ever did–the ball just takes longer to get to home plate ”

Feller is the camp commissioner at the Cleveland Indians Fantasy Camp held every January at the Indians spring training facility in Winter Haven, Florida. His job is to spend a week in the Florida sun playing and talking baseball with camp participants. Feller coaches and oversees the participants activities, which include seven games of baseball, a photo day, a video day, an awards banquet, and the opportunity to whack baseballs with real wood bats.

He is also still a fixture at the Cleveland Indians spring training camp, putting on a full uniform and throwing out a few ceremonial first pitches for the teams spring training games.

“I hoist up my pants from my old Indian days,” Feller said, “so my pant legs rise above my knees. That way I look like a real baseball player. Players today wear their pants down to their shoes, making them look like they’ve got on pajamas.”

The Picnic Pavilion behind the third base stands is Feller’s hang out during spring training. He signs autographs there. It’s five dollars to get an item signed–unless you buy his Little Black Book. Then, he signs the book for free. Fans say the wait for Feller to sign an autograph at spring training is long because he does not run an assembly line autograph session like some players do. Feller spends time with fans, he answers questions, poses for pictures and shakes hands.

Feller’s other important connection to baseball is his namesake museum, which he visits several times a year. Built in 1998 through a community fund-raising effort, the museum is located 12 miles west of Des Moines in his home town of Van Meter. The museum collection includes artifacts from Feller’s childhood, major league baseball career, military service. and Hall of Fame induction_ Items from Feller’s three no-hitters are on display, along with the bat that Babe Ruth leaned on when he said good-bye to the fans at Yankee Stadium on June 13, 1948. One of my favorite items is a homemade arm warmer. Bob’s mother made it out of an old gunnysack. During his early years with the Indians, Feller wore it between innings whenever he pitched.

At the end of my interview with Feller, we went upstairs to the museum. Two middle-aged women from Ocala, Florida, were touring the displays. They had come to Omaha for the College World Series and had driven two hours to Van Meter just to see this piece of American history. When one of the women noticed Feller, she cried out.

“Bob Feller ?! My uncle, Paul Brownell, was your catcher on the Des Moines Farmers’ Union team in 1935!”

Feller grinned from ear to ear. He walked over to the women, chatted awhile, then posed for a picture with them. He spent time with them, reminiscing. Later, I asked Feller one last question: “If you could relive any one of the many great moments in your life. which one would it be?”

Feller didn’t hesitate.

“Playing catch with my dad between the red barn and the house.”